Resistance in Cleveland

Additional Information about these Anti-Slavery and Underground Railroad Activists

-

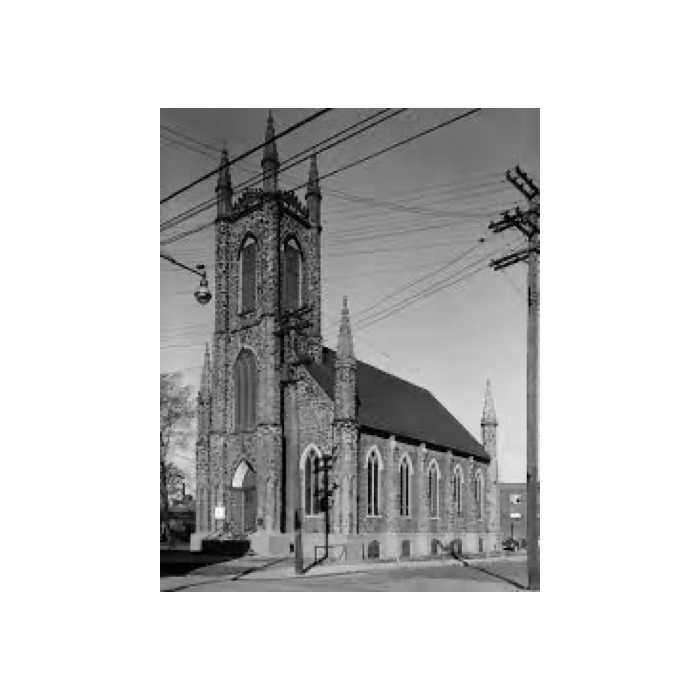

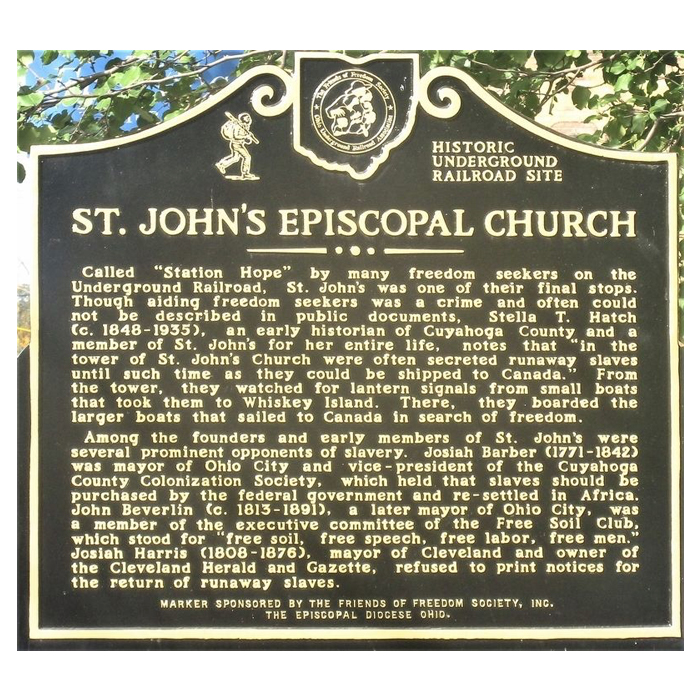

A. St. John’s Episcopal Church

A safe station for freedom seekers awaiting transport to Canada; called “Station Hope”

Located on the corner of Church Street and W. 26th Street on Cleveland’s near west side, St. John’s Episcopal Church was built between 1836 and 1838, making it the oldest consecrated building in the Cleveland area. A founding member of the parish, architect and master builder Hezekiah Eldredge, oversaw its construction of gray sandstone in Gothic style.

Several early organizers of the parish, including Judge Josiah Barber, Charlotte and David Griffith, and Benjamin Beverlin, are known to have been either sympathetic to or active in abolitionist activities.

In the mid-1800s, parishioners housed fugitive slaves in the church’s bell tower, awaiting a signal that it was safe to proceed to the Cleveland docks and board ships for Canada. The church’s code name on the Underground Railroad was “Station Hope,” based on the code name for Cleveland—“Hope.”

Because assisting freedom seekers was illegal, written records were not kept at the time. Around 1900, Stella T. Hatch, second generation relative of founder Judge Barber, recorded stories and information which had been handed down in her family, supplying some detail about the role of St. John’s on the Underground Railroad.

In recent years, Cleveland Public Theatre has co-hosted with St. John’s an annual multi-arts block party called “Station Hope” which celebrates the freedom-seekers’ bravery and encourages community engagement in current civil rights issues.

-

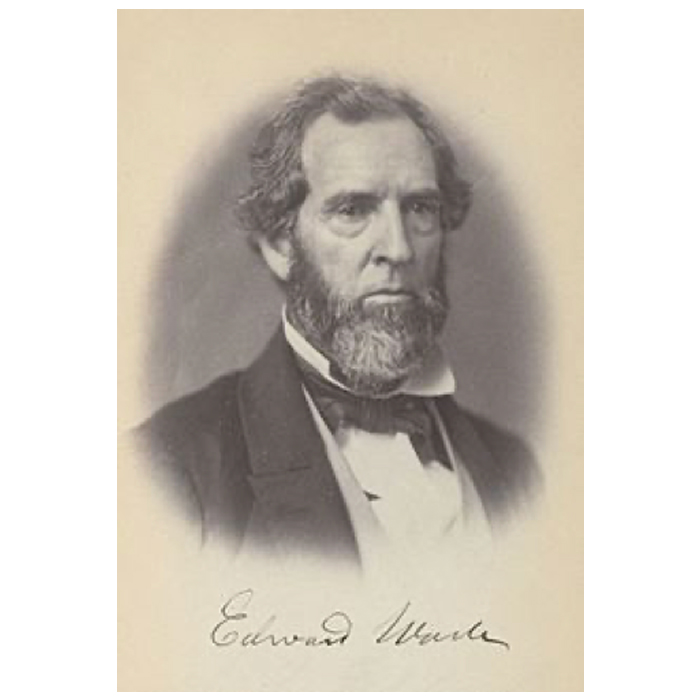

B. Edward Wade (w)

His tavern served as a west side station for freedom seekers; he served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1853-1861

Edward Wade (1802-1866) was a lawyer, admitted to the bar in 1827. He practiced law in Ashtabula County, becoming a Justice of the Peace and a prosecuting attorney.

In 1837, he moved to Cleveland, where he continued practicing law and became one of the area’s leading abolitionists.

Wade settled on a farm south west of Cleveland in Brooklyn Township. His first wife,

Sarah Louise Atkins, died. Her father, Quintus F. Atkins, lived on Wade’s farm from 1839 on. Wade later married Mary P. Hall. There were no children in either marriage. -

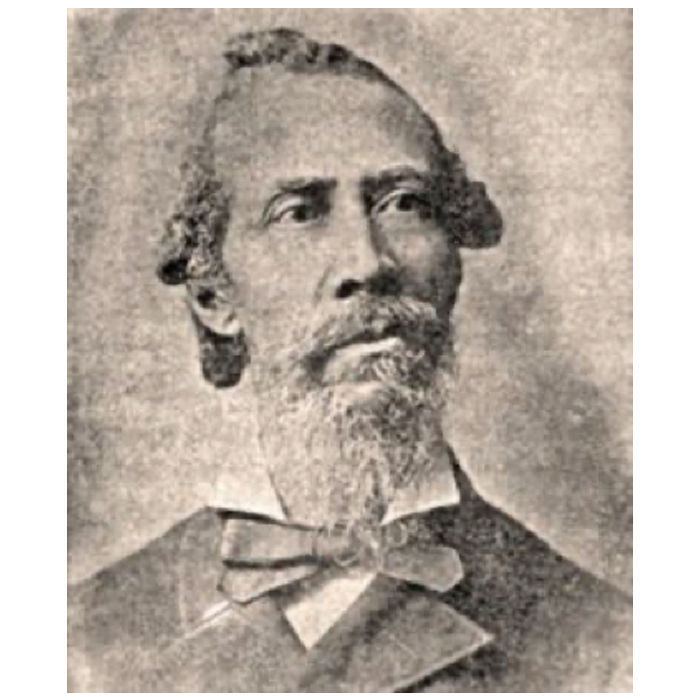

C. William Howard Day (b)

Editor of the first black newspaper in Cleveland, The Aliened American, he lived on Bolivar Road with Lucy Stanton Day, the first black woman to graduate from Oberlin College

William Howard Day (1825-1900) was born in New York City where, after his father died when he was four, his mother struggled to support her four children and secure them proper educations, especially for William, who was a precocious youngster.

His intellectual potential came to the attention of J. P. Williston, an affluent white manufacturer and abolitionist, in 1828. Williston offered to adopt the talented youth and pay for his education. For the next five years, Day lived with the Willistons in Northampton, Massachusetts, completed his secondary education, and learned the printing trade on the side.

Williams College denied him admission after southern students protested the idea of studying alongside a person of color, so Day enrolled in Oberlin College. In the fall of 1843, he was the only African American among the fifty students entering the first year of the College Course. At Oberlin, he was a leader in the town and at the college, speaking out against slavery and supporting abolition.

After graduation, he worked to repeal Ohio’s Black Laws, was a delegate to the 1849 Mass Convention of Colored Citizens of Ohio in Columbus, and helped organized the Negro Suffrage Society.

In 1851, Day relocated to Cleveland, where he published The Aliened American, Cleveland’s first black newspaper, taught Latin, Greek, math, and rhetoric, and was appointed librarian of the Cleveland Library Association.

He also married Lucy Stanton, whom he had known at Oberlin, where she as the first black woman to complete the four-year college course.

Lucy was the step-daughter of John Brown, a prosperous African American barber who was extremely active in Cleveland anti-slavery and Underground Railroad activities. (Not the John Brown of Harper’s Ferry fame) When Lucy had been denied a place in the Cleveland neighborhood school because of her race, her step-father paid for the construction of a school for Cleveland’s children of color.

The Days left Cleveland for Buxton, Canada, in 1856 to help educate fugitive slaves who had relocated there. Then William and Lucy’s ways parted, with him going to England to raise funds and she returning to Cleveland.

After the Civil War, both were active in the advancing of the education and rights of freedmen, teaching and even funding schools in the south and in eastern Pennsylvania. She eventually remarried (Levi Sessions). In 1866, Day was ordained a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion church.

-

D. John Brown (b)

For over 40 years he operated a barbershop near Public Square; he used his own resources to support the Underground Railroad in downtown Cleveland

This John Brown (c. 1798-1869) was born to free black parents in Virginia and came to Cleveland in 1828. He was a barber in Cleveland’s downtown hotels for over forty years and became one of Cleveland’s wealthiest African Americans through real estate investments. Historians often refer to him as “John Brown, the barber” to differentiate him from the white John Brown who was an activist against expanding slavery to the Northwest Territory and led the ill-fated raid on Harper’s Ferry. Cleveland’s John Brown was active in the black community’s social life, participating in debates before the colored Young Men’s Union Lyceum.

He was acknowledged as an intelligent and formidable barbershop conversationalist on politics, religion, and philosophy. He literally “had the ear” of his wealthy white clients as they sat in his barber chair, where he could hold bi-racial conversations without arousing suspicion. So he was also able to quietly discuss Underground Railroad plans with local abolitionists and friendly ship captains. His shop often served as the last stop for fugitive slaves before they embarked on a lake vessel to freedom.

Brown married Margaret Stanton, widow of a fellow barber. When his step-daughter, Lucy Stanton, was barred from the local school because of her race, Brown worked with John Malvin and other Cleveland blacks to organize a school for the city’s African American children. For a period, he maintained the school largely at his own expense. Lucy went on to be the first black woman to complete the Ladies Course at Oberlin College, and married William Howard Day.

During the Civil War, Ohio initially refused to enlist black troops, so Brown’s sons, John and Charles, went to join a black regiment in Massachusetts.

Brown and his wife are buried in Woodland Cemetery.

-

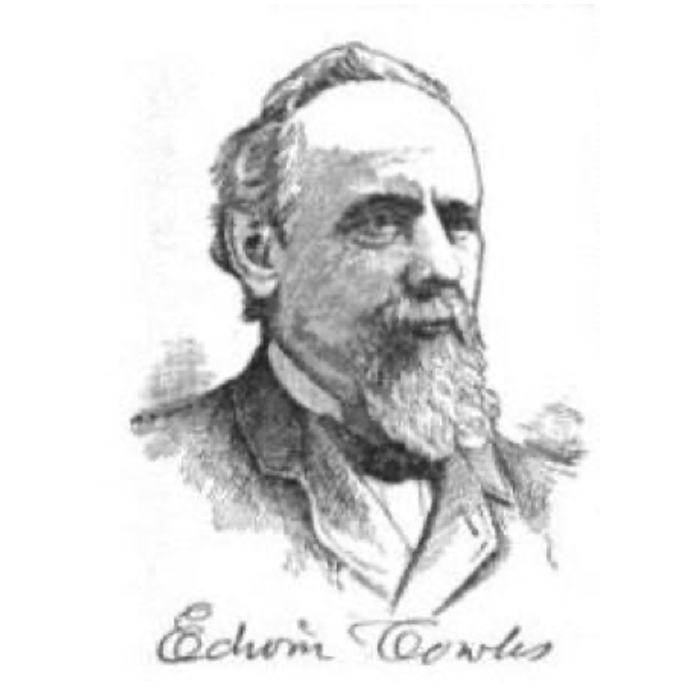

E. Edwin Cowles (w)

The editor of the Morning Leader, a Cleveland newspaper that supported the abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad

Edwin Cowles (1825-1890) was born in Austinburg, Ohio, and came to Cleveland in 1839 as a printing apprentice.

In 1844, he and Timothy Smead formed a printing partnership. Acquiring and merging several existing newspapers, they established the Cleveland Leader in 1854.

Cowles led the Republican party in Cleveland and, when he became editor of the Leader, made it the radical Republican voice.

After the Republican victory in the elections of 1860, he was named Cleveland postmaster. He pioneered free mail delivery. Later, under President Andrew Johnson, he was replaced as postmaster by George A. Benedict, editor of the more moderate Herald.

At the end of the Civil War, the Leader was the best-selling daily newspaper. It was organized as a joint stock company on July 3, 1865. Its evening edition, begun in 1861 as the Evening Leader, was renamed the Evening News in 1868. By 1875, its circulation of 13,000 was double that of the Herald and five times that of the Plain Dealer.

Cowles kept the paper technologically up to date, importing Cleveland’s first perfecting press in 1877 and pioneering the use of electrotype plates in Ohio. Together with the Plain Dealer, in 1885 the Leader bought out its old rival, the Herald. Editorially, the Leader was an extension of its editor’s strong personality.

-

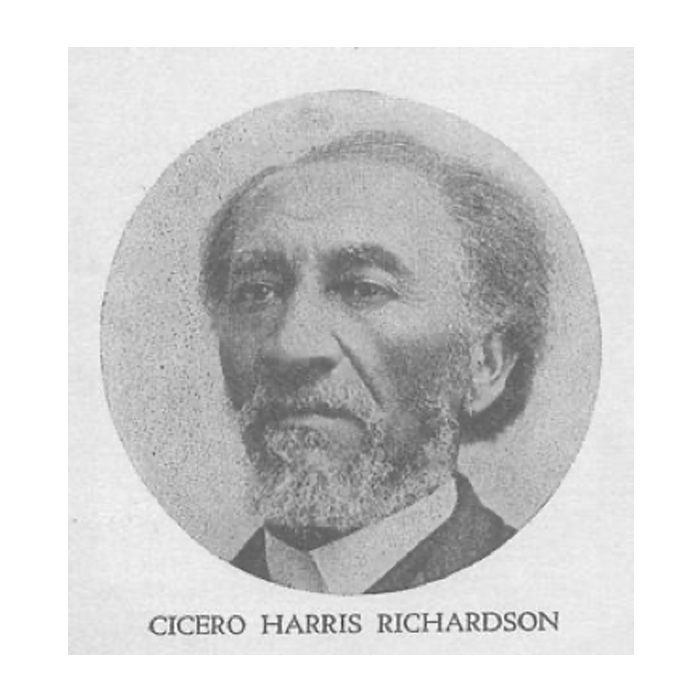

F. Cicero Richardson (b)

Plasterer by trade, he lived a few blocks east of Public Square and was active in the Underground Railroad

Born about 1818 in North Carolina, Cicero Richardson married Sarah Ann B. (Harris) Richardsonon December 16, 1841, in Fayetteville, NC. After relocating to Cleveland, Richardson was a conductor on the Underground Railroad in the 1850s.

On January 25, 1861, Richardson was at a railroad station along with George Vosburgh and other colored people of the city attempting to rescue Sara Lucy Bagby from being returned to slavery under provisions of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law. The “rescue” was not successful when the policemen clubbed them back. Richardson was struck over the head sustaining injuries from which he never fully recovered. He sued the Federal Marshalls.

-

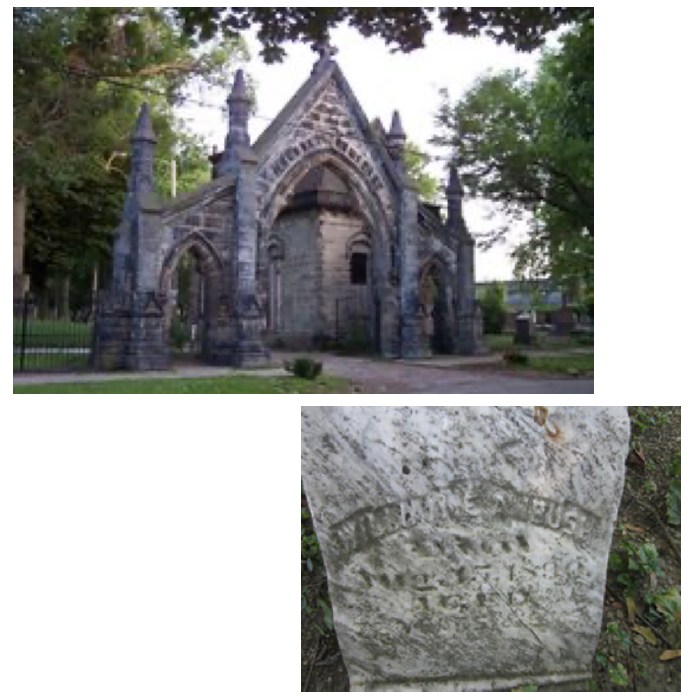

G. William Ambush (b)

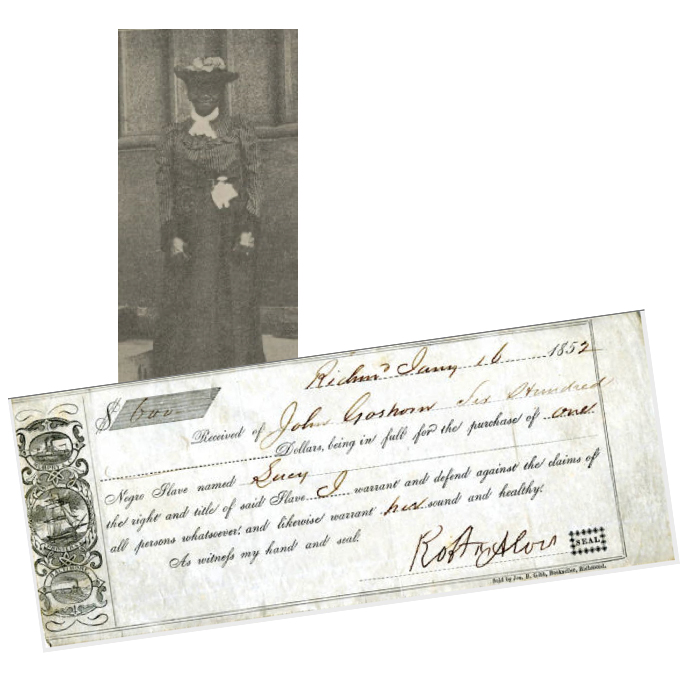

Barber at the American House hotel, he was head of the Vigilance Committee; he and his wife sheltered Sara Lucy Bagby

William E. Ambush (1818-1890) was chairman of the Fugitive Aid Society in Cleveland. This group’s public stand was to assist slaves who had escaped to free states. Members helped supply them with food, clothing and money. In urban areas, the Vigilance Committees did virtually the same work, as well as provide legal counsel and medical attention. They also “kept vigil,” watching for slave catchers in the area and spreading warning of their presence. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, this was considered Underground Railroad activity. As a barber in a downtown location, Ambush was well placed to learn and pass on relevant information, even while he was at work.

Ambush and his wife Maria helped Lucy Bagby during the years she was in Cleveland, having run away from her owner, William Goshorn, in Virginia.

After Bagby’s arrest on January 19, 1861, Ambush offered to raise $1,200—double what the Goshorns had paid for her in 1852—and “purchase” her to secure her freedom. The Goshorn family was worth approximately $300,000, so their legal victory of forcing Lucy’s return motivated them to refuse the offer and retain Lucy as their possession.

Ambush then moved to legal tactics, swearing an oath against the sheriff and jailer because Lucy—a runaway / victim—could not legally be held in a jail, which was meant to house criminals.

Probate Judge Daniel R. Tilden issued a writ of habeas corpus on her behalf, based on this argument.

However, since the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 made it illegal to escape from bondage, the court determined that Lucy was indeed a criminal because she had stolen herself from the Goshorns. Since they had documentation proving ownership, Lucy was sent back to Virginia with the Goshorns.

She is believed to have been the last runaway returned to the south before the outbreak of the Civil War three months later.

Ambush’s wife, Maria, died in 1870 and is buried in Woodland Cemetery. Historians have identified her gravesite, but there is no headstone.

Ambush died in 1890 and is buried in Monroe Cemetery, 3207 Monroe Avenue, on Cleveland’s near west side.

-

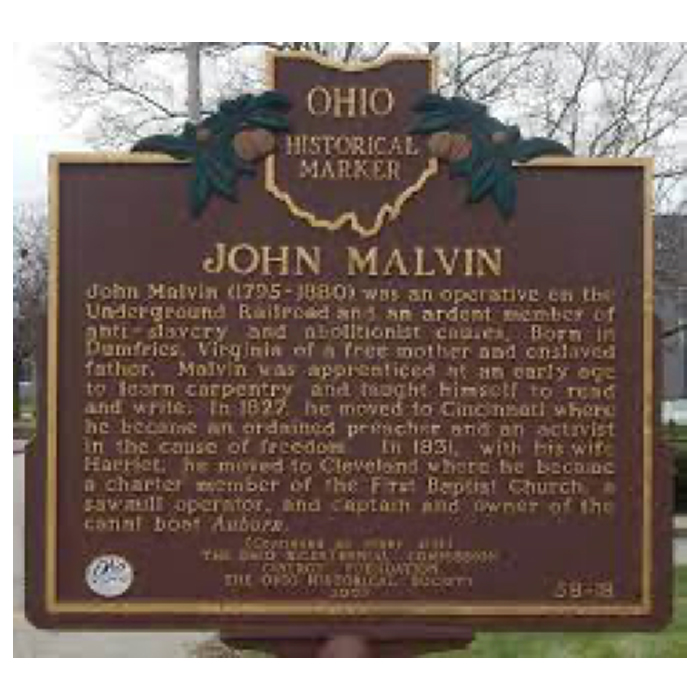

H. John Malvin (b)

A charter member of the First Baptist Church, he fought for funding for schools for black children and organized black units at the start of the Civil War; active in the Underground Railroad

John Malvin (1795-1880) was born to a free black woman and enslaved father in Virginia. Free himself, he was “apprenticed” to his father’s owner and worked side by side with his slaves. Malvin’s father taught him carpentry, and he learned to read in secret. He read the Bible and became involved in religious meetings, sometimes even preaching.

In 1827, he obtained official “free papers” and walked all the way to Ohio, where he came up against its discriminatory Black Laws. Malvin settled first in Cincinnati, where he helped some slaves he had known escape to the UGRR from a riverboat where they were being held. Unhappy with conditions for blacks in Cincinnati, he and his wife planned to relocate in Canada. They got as far as Cleveland, but did not cross the border because they wanted to secure his wife’s father’s freedom first.

Malvin’s race kept him from a job in his trade of carpentry. He got a job as cook on the lake schooner Aurora, where he was also able to learn maintenance of the ship’s boiler. To buy his father-in-law’s freedom, he purchased The Grampus, which carried cargo on Lake Erie. Doing this, he was able to finish paying the price for his father-in-law. He then sold the boat. For a number of years he owned and captained the Auburn on the Ohio Canal, carrying freight, paying passengers, and runaways.

Having become a known and respected member of the community, Malvin was finally able to find work as a carpenter. He helped build First Baptist Church, an integrated congregation of which he was a member. While he helped build the church’s pews, he and the other black congregation members were assigned seating in the balcony, segregated from the white members’ pews on the main floor. It took him nearly a year to convince the church’s leadership to truly integrate the congregation by giving its black members pews scattered around the main floor, mixed in with the white members.

Malvin was an activist and an advocate for the civil rights of black citizens. Starting when he was in Cincinnati, he was vocal in petitioning for the repeal of Ohio’s Black Laws. With John Brown (the barber) and others, he financed a school for colored children (and some adults) in Cleveland and, in 1839, organized a Young Men’s Union Society to promote reading and debating.

Malvin was a spokesman and participant in state-wide colored conventions, which met every few years, and often spoke at these and other public gatherings. In individual cases, he worked closely with others in the community to sponsor black families attempting to move to Ohio by posting the bond required by the Black Laws and then helping them find work and a place to stay. He also posted bail for runaways who had been arrested and helped locate white witnesses who could testify in court on their behalf, since the Black Laws prevented blacks from testifying, even in their own defense. Together, these advocates managed to keep a number of blacks who had arrived in Cleveland, some of them already free, from being returned south.

Malvin wrote an autobiography, North Into Freedom, in which he details some of the challenges he faced as he tried to integrate into life in the north. He also tells some compelling stories of his work on behalf of civil rights for all.

An Ohio historical marker identifies the site of Malvin’s last residence in Cleveland at 2320 East 30th Street in what was at the time an upper-income neighborhood of Cleveland. East 115th Street, off Mayfield, has been named John Malvin Way, also recognizing his role in Cleveland’s history.

Known to many has “Father John,” Malvin died at his home and was buried in Erie Street Cemetery, 2291 East 9th Street (formerly known as Erie Street).

-

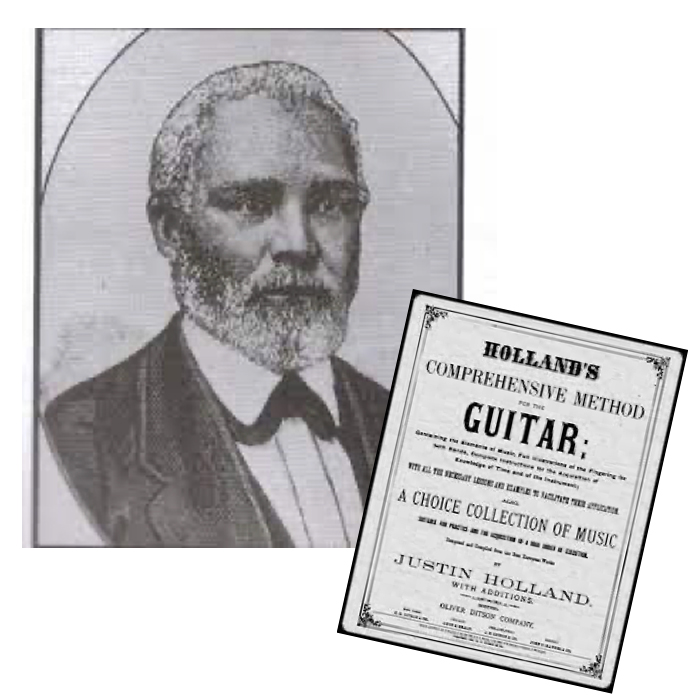

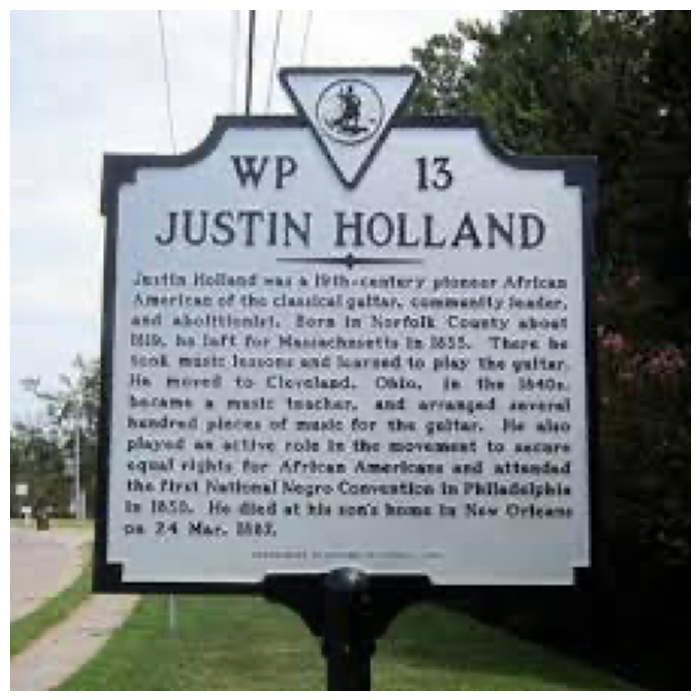

I. Justin Holland (b)

Internationally known musician who was active in the Underground Railroad in Cleveland and in the 1848 National Convention of Colored Freemen

Justin Holland (1819-1887) was born to free black parents in Norfolk County, Virginia. He showed early talent for music, writing music for pre-existing lyrics, but was limited to the church for musical opportunities.

An orphan by age 14, he moved near Boston, Massachusetts. Supporting himself as a laborer, young Holland was able to take guitar lessons from Signor Mariano Perez and William Schubert, and practice arranging music with Simon Knabel.

Starting in 1841, he studied at Oberlin College for two years. Wanting to focus on Spanish classical guitar music, he traveled to Mexico to learn Spanish so he could read the methods books written by several master Spanish guitar teachers.

Returning to Oberlin in1845, he married and moved to Cleveland, where he gave guitar lessons and arranged music like popular songs and opera arias for the guitar. His collections of arrangements and music method books were sold nationally to those who shared the conservative approach of the European guitar masters and their traditional techniques.

A CD of some of his original compositions and other arrangements is often played at the Cozad-Bates House Interpretive Center when it is open on Saturday afternoons. If it is not playing and you would like to hear it, just ask a docent.

Holland’s consummate professionalism was visible evidence debunking the concept of “racial inferiority” being used by slave holders, who needed this justification to keep their laborers producing cotton.

In Cleveland, Holland not only embodied education and assimilation as a route to racial equality, but also for civil rights on local and national levels.

Between 1848 and 1854, he was an assistant secretary and member of the council at National and State Negro Conventions. He quietly worked with the Underground Railroad as well, and was secretary of the Central American Land Company, working toward the establishment of a free black colony there.

National Public Radio (NPR) aired a documentary on April 17, 2022, on Justin Holland: The Classical Guitar and Black Pioneer. Produced with a grant from National Endowment for the Arts, it featured Professor Ernie Jackson of Queensboro Community College, a Holland expert, and Professor Robert Anderson, also from Queensboro College, in dialogue with host Scott Blankenship. Stories about Holland’s life and contributions were interspersed with Holland’s music played by contemporary guitarists. Selections included arrangements of classics such as “Home Sweet Home,” “William Tell Overture,” and Verdi’s “La Traviata” as well as Holland’s original compositions like “Martha,” “Elfin Waltz,” and “Last Waltz of a Lunatic.” Jackson spoke to the significance of Holland’s music for his African American students, who realize that not all classical music was created by long-dead white European men.

An historical marker in Chesapeake, Virginia, has been erected to honor their home-town musician from the nineteenth century.

-

J. Alfred Greenbrier (b)

An Ohio City horse trainer, he supplied horses to freedom seekers

Alfred Greenbrier (1808-1888) was a freed slave from Clark, Kentucky, who arrived in Cleveland in the 1820s. He became widely known for raising horses and cattle.

Greenbrier was one of the first African American property owners in the City of Cleveland, and his house at 4019 Bridge Avenue still stands and has been remodeled. It is a private residence.

Greenbrier married Ianza (“Ann”) Brown Greenbrier and they had seven children. He is buried in Cleveland in the Monroe Street Cemetery, 3207 Monroe Avenue, on Cleveland’s near west side.

-

K. Robert Leach (b)

The first African American doctor in Cleveland, he practiced on Walnut Street; he was also a delegate to the 1853 Convention of Colored Freemen in Columbus

Robert Boyd Leach (1822-1863), Cleveland’s first black physician, was originally from Virginia. He first moved to southern Ohio, then in 1844 to Cleveland. As a young man, he worked as a nurse on the lake steamers during navigation season.

He first learned about medicine entirely from books, then entered Western Homeopathic College, receiving a degree in homeopathic medicine in 1858. He established a medical practice in Cleveland, treating both white and black patients. He is credited with a specific remedy to treat cholera, which was successfully used throughout the region.

Leach was a spokesman for blacks, and was frequently mentioned in news items relating to the struggle of blacks in Cleveland. He was on the executive board of the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society.

During the Civil War, he helped recruit black soldiers for the Union Army, but was not accepted for service himself because the army was not taking doctors trained in homeopathic medicine. He then began to study allopathic medicine, but died a few months later of a liver ailment.

-

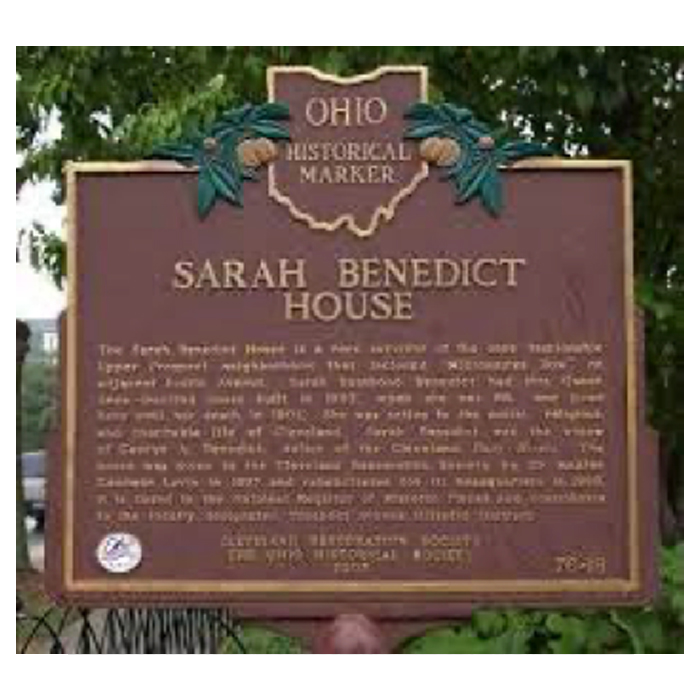

L. George Benedict (w)

Publisher of the Cleveland Herald, which was sympathetic to abolitionist activities and the Underground Railroad

George A. Benedict (1812-1876), originally from Watertown, New York, moved to Cleveland in 1835, shortly after his admittance to the bar. He practiced law for several years, also serving briefly as city attorney and president of the city council. From 1848 to 1851, he was clerk of the superior court.

In 1853, Benedict purchased an interest in the Cleveland Herald, to which he had previously contributed articles. In 1857, he became its editor and kept the paper on a course of conservative Republicanism throughout the Civil War and Reconstruction. The Herald’s readership gravitated during these years to the aggressive Republicanism of the Cleveland Leader, edited by Edwin Cowles.

Cowles was appointed postmaster of Cleveland, a coveted position, but was replaced by Benedict under Andrew Johnson’s presidency.

Seven years after Benedict’s death in 1876, his widow, Sarah Rathbone Benedict, built a stately brick home at 3751 Prospect Avenue in Cleveland. After years as a single family home, and eventually a student bar, the house was renovated.

The Sarah Benedict House is now the headquarters of the Cleveland Restoration Society.

-

M. Elizabeth Gould (b)

Owned a boarding house near the docks which provided safe haven for freedom seekers

Wilbur Siebert recounted information about Elizabeth Gould in The Mysteries of Ohio’s Underground Railroad, which he compiled from thousands of late-nineteenth-century interviews.

On page 272, Gould, whom he calls “Betsy Gould,” was the keeper of a boarding house for negroes on Erie Street between Bolivar and Eagle Streets in downtown Cleveland. Underground passengers who arrived from Delaware, Ohio, via the Cleveland, Columbus & Cincinnati Railroad were directed to take rooms with her until they could be gotten to the Cleveland wharf.

According to Siebert’s sources, in the spring of 1853, a committee of Cleveland abolitionists, namely Tower Jackson, Mr. Smith, a Presbyterian minister, and a Mr. White, moved Betsy’s customers to other quarters, alleging that she was “tricky.”

Jackson saw them on board the packet for Detroit, paying part of their fares, the rest being paid by them. Near the Central Depot in Detroit, fugitives stayed at a tavern for negroes until they crossed to Windsor, Canada, on the ferry-boat.

-

N. Juliana Long (w)

Active in the anti-slavery movement along with her husband David Long; David Long was the first doctor in Cleveland and founded the Cleveland Anti-Slavery Society

Juliana (Julia) Walworth Long (1794-1866) was born in Aurora, New York. Her family moved west to Painesville in 1800, then to Cleveland in 1806. On April 11, 1811, she married David Long (1787-1851), the first permanently-settled physician and only doctor in Cleveland until 1814.

During the War of 1812, Long was a surgeon in the Western Army, and in 1824 became the first president of the Society of the State of Ohio’s 19th Medical District, forerunner of the Academy of Medicine in Cleveland. Long was also quite involved in business, and in 1833, he became president of the Cleveland Anti-Slavery Society.

The Longs lived on Water Street (West 9th), later the site of the city light house, then moved in 1813 to a large log cabin built by Samuel Huntington. In the 1830s, they lived on a farm in Kinsman, which was later the site of St. Ann Hospital. In 1845, they moved to a brick home at Longwood and Kinsman Road.

With her husband, Juliana gave medical care to the poor. During the War of 1812, she served as a nurse and he as a surgeon for wounded soldiers brought to Cleveland. She also worked with the homeless, and took orphans into their home.

Both are buried in Woodland Cemetery.

-

O. James Thome (w)

An Oberlin graduate and professor, he relocated to Ohio City and served as a local pastor; he became a national figure in the abolition movement

James A. Thome (1813-1873) was born in Augusta, Kentucky, the son of Arthur Thome, a slaveholder with a flourishing flour mill. After receiving a basic education at Augusta College in Kentucky, Thome taught for a while a various schools in the Northeast. During this time he became a supporter of the abolitionist cause. His decision to become an abolitionist put him at odds with his slaveholding father, who initially disowned him. The two of them were later reconciled, however, and Arthur Thome emancipated his slaves in 1834-38.

Young Thome entered Lane Seminary in Cincinnati in 1833 and took part in the 1833 and 1834 debates organized by Theodore Weld on the slavery question. Thome delivered a speech supporting immediate abolition, based on his personal experiences as the son of a southern slaveholder. Thome was among the thirty-two seminary students who left Lane Seminary and transferred to Oberlin College, from which he graduated in 1836.

Soon after his graduation, Thome was commissioned along with J. Horace Kimball, editor of the Herald of Freedom, by the American Anti-Slavery Society to observe and report the effects of emancipation in the West Indies. The two spent six months in Antigua, Barbados, and Jamaica. Their account, Emancipation in the West Indies, was published in 1838 and served as an influential abolitionist text.

On September 25, 1838, Thome married Ann T. Allen, who had attended Oberlin from 1835 to 1836. Also in 1838, Thome accepted a position as Professor of Rhetoric and Belles Lettres at Oberlin, which he held until 1848. In 1851, he was elected to the Oberlin College Board of Trustees.

Thome left Oberlin in 1848 to become pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Brooklyn, Ohio, in Ohio City. The church later became First Congregational Church. He served that congregation until 1871. During this time he also wrote for various antislavery papers and served as a special correspondent for the Cleveland Leader. He also worked as an agent of the American Missionary Association in England and Scotland in 1867 and 1868, raising money for freed people.

From 1871 until his death, Thome served as pastor of the First Congregational church in Chattanooga, Tennessee. He died on March 4, 1873 from pneumonia.

-

P. George Pierce (w)

Steamboat agent; he assisted the Underground Railroad along river and lake docks

Information about George Pierce appeared in a letter from Miss Marion LaMere, Andover, Massachusetts, dated April 2, 1935:

The Hon. George W. Morrill (born in Amesbury, Massachusetts) moved to Cleveland in 1851. He operated a “car shop” until he retired in 1867. According to Miss LaMere, Morrill was sent “consignments of fugitives” with whom he met and then stowed them on board steamboats at the Cleveland docks.

“Captain Pierce was the agent of a steamboat company and also an ardent Democrat. On the dock, he supervised the shipment of freight. Knowing Mr. Morrill’s reputation as an Underground agent, he often cautioned him: ‘Morrill, if I ever see you taking negro slaves into my boats I will certainly deliver them up.’ But when Mr. Morrill approached with the fugitives, the captain would deliberately turn his back so as not to see them.”

So, while he was not actively escorting freedom seekers himself, Pierce was enabling their transfer to the ships by those who were by intentionally overlooking the incidents.

-

Q. L.A. Benton (w)

Hired runaway Sara Lucy Bagby in 1860-61 to work in his home on Prospect Street in downtown Cleveland

Information about George Pierce appeared in a letter from Miss Marion LaMere, Andover, Massachusetts, dated April 2, 1935:

Lucius A. Benton (1827-1913) was born in Burton, Ohio. He is listed in 1880 census records as a jeweler. He was working in the 1840s with Crittenden, Benton & Maihivet in Cleveland as a jeweler, watchmaker, and silversmith, a career he appears to have pursued for four decades.

He and his wife, Martha A. Leslie Benton (1827-1907), had three children, Ella, Clara, and Frank. They lived at 151 Prospect Street.

It was at his residence that fugitive Lucy Bagby was arrested on January 19, 1861. She had been working as a domestic servant for the Bentons for nearly two weeks, after it was deemed politically prudent to move her from the home of Congressman-Elect Albert G. Riddle, where she had been working. Riddle’s credibility in his up-coming legislative role would have been seriously compromised if he had been caught harboring a runaway in his home. Cleveland’s Underground Railroad community arranged Bagby’s transfer to Benton’s home, making him an UGRR station master.

The Bentons are buried in Lake View Cemetery.